The Man Who Did Zilch

In our Lukewarm War with Russia, any glitch in both sides' early warning systems can accidentally trigger the Doomsday Machine. Just like in September 1983–if it hadn't been for an unlikely hero.

Actually, what were you doing on the night of September 25/26, 1983, while the big clock in the Kremlin's Savior Tower struck midnight? Of course, I'm only asking in case you weren't “pudding in the shop window”, as those not yet conceived at any given time are strangely called in my home. So if you were already on earth, or in Western Europe more specifically, chances are you were lying in bed and sleeping. After all, you had to be fit for the new working week, school or kindergarten when the alarm clock rang on Monday morning. Maybe you had even just brushed your teeth. Moscow’s time zone was an hour ahead of Germany’s.

I, for one, will have been busy dreaming, falling asleep or … well, okay. I was 17 years old and didn't have a girlfriend. What I did have was a room in my parents' house and puberty pimples. Life was uneventful and revolved around high school, music, mates and a general lack of understanding of the world.

My ignorance was a blessing, as I know today. Because above all, I had no idea. I share the good fortune of having survived that night with almost all of you who were born back then. But only today, a little more than forty years later, do I realize what a tremendous miracle that is.

The man to whom we middle-aged people owe this miracle died in May 2017, but this only became public knowledge months later. The vast majority of us will not know his name, let alone have ever met him. He was Stanislav Yevgrafovich Petrov, he was 44 years old on the night this story is about, and he was a lieutenant colonel in the Soviet Red Army.

Ranking as a staff officer, Petrov held a strategic position in the USSR's still relatively new satellite-based early warning system against nuclear missile attacks by the USA. He served in a bunker facility called Serputschow-15 near Moscow. It was the command center for the satellites of the “Oko” network, the Russian word for “eye”. Petrov's task was to finally verify the authenticity of the data in the event of an automatic attack alert from one of the Oko satellites. Next, he would notify his superiors. They in turn would then trigger the inevitable Soviet counter-attack–the second act of World War III.

Petrov was not scheduled for duty that night, but he stepped in at short notice for a colleague who had fallen ill. The atmosphere in front of the control monitors was tensely concentrated, because just like today, Washington and Moscow were at a low point in the Cold War. In recent years, both superpowers had attempted to strengthen their zones of influence through military interventions in Central America and Afghanistan respectively. US President Reagan branded the Soviet Union an “Evil Empire”. To counter modern Soviet nuclear missiles of the SS-20 type, Nato decided to deploy Pershing II missiles in Western Europe. The Strategic Defense Initiative (SDI) for a nuclear missile defence shield in space was hatched.

And it was only at the beginning of September 1983, a good three weeks before Petrov's unscheduled entry into service, that a MiG interceptor shot down Korean Airlines Flight 007 over international waters, a passenger jet with 269 people on board. The pilot had inadvertently violated Soviet airspace. The Russians expected an enemy incursion into their territory at any time. Was there anyone in the concrete bunkers of Serputschow-15 who did not believe that the USA might go for a surprise nuclear first strike? At 00:15 Moscow time, something happened that would settle that question.

A piercing alarm sound signaled that a US nuclear missile had risen from its silo in the Midwestern United States, headed for the Soviet Union. The Oko satellite over the region had registered the typical “heat signature” of a missile launch. The computerized analysis system had 30 levels of automatic verification built into it. And yet it had triggered the alarm–with the highest level of reliability.

In such a situation of extreme stress, soldiers are drilled to follow the practiced protocol like robots. This involved double-checking the integrity of the satellites and computers. Petrov instructed his team to examine the algorithms using printed pages of code. He then asked the specialist for visual evaluation, “Do you see anything on the monitor with the live satellite images? Is there a telltale contrail somewhere over the USA?

But the specialist saw nothing.

–“Does that mean there's nothing there?”

–”No, it means I can't see anything!”

–”But can you rule it out?”

–”No, I can't. I just can't see anything!”

Visibility in the high layers of the atmosphere is deceptive.

An intercontinental missile launched from the US took less than 15 minutes from its silo to reach the territory of the USSR. The second hand ticked. Petrov had to make his report: nuclear attack–yes or no? He picked up the red telephone and reported: false alarm. No attack. He had always distrusted the satellite system, which was known to be susceptible to interference. Moreover, he had internalized one thing during his training: If the USA attacked, the strike would be massive, with hundreds of missiles approaching simultaneously. This was the only way to ensure that most of the enemy infrastructure would be destroyed despite the inevitable counter-attack. A single missile made no sense.

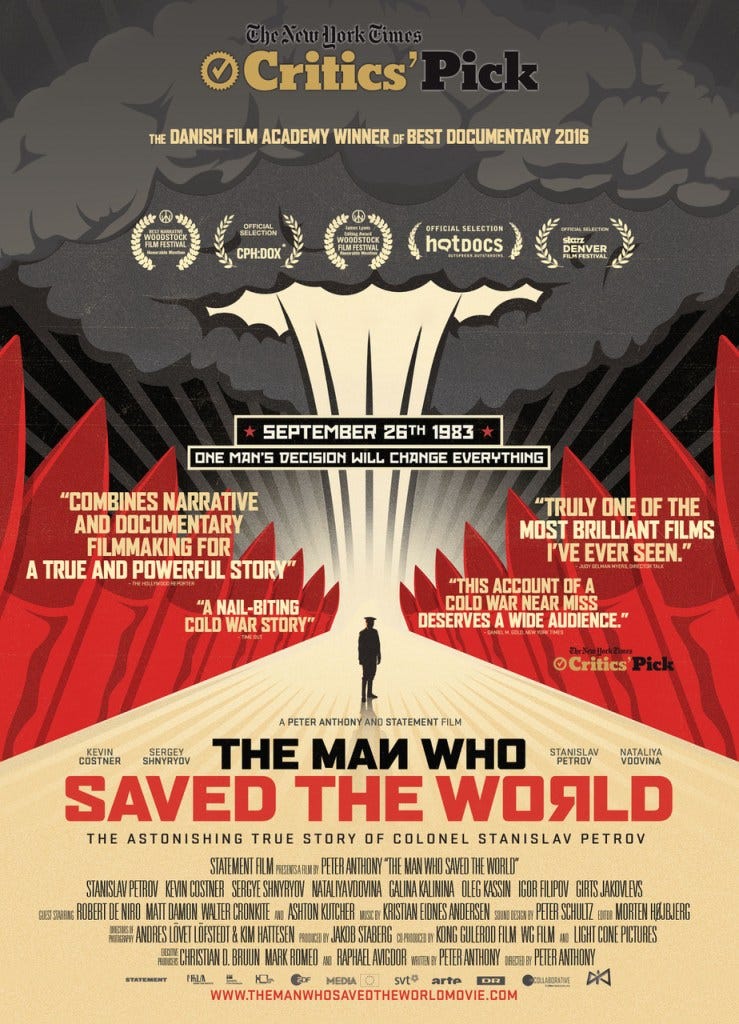

As for Petrov reporting a false alarm, that is how it is portrayed in the movie “The Man Who Saved The World”, a docu-drama by Danish director Peter Anthony from 2014. Anthony uses actors to depict the situation in 1983, while the real Petrov, who has aged a quarter of a century, can be seen and heard in the retrospective parts. However, some critics question the truthfulness of this film. They also consider the all too perfectly captured images in the supposedly documentary parts to be scripted reality, a fabricated version of the actual events. Petrov merely followed the instructions and lines of dialog in the script presented to him, the accusation goes.

It is said that the retired soldier's need for money in post-Soviet Russia led him to sell his soul to the filmmakers. There are even suspicions doing the rounds on the internet that Russia secretly co-financed the lavishly produced film in order to create a propaganda image of heroic peacekeeping. The fact that Petrov made a report at all because of a singular missile warning is also disputed by some. It could just as well be that he simply did zilch. Perhaps he never got around to it.

Because just two minutes later, all hell broke loose in the command bunker near Moscow. Every minute between 00:17 and 00:20, the “Oko” satellite system reported an additional missile launch from US soil–each again with the highest “verification level”. A total of five nuclear intercontinental ballistic missiles of the “Minuteman” type with multiple warheads were now allegedly inbound. This is consistent with most other reports from that night.

At one point, Anthony's “documentary” shows the 70-year-old pensioner Petrov visiting the USA, where he is to be awarded a prize for his historical heroism. During this tour, he also visits the only Minuteman silo open to the public and inspects the most modern version of the enemy's deterrent weapon for the first time.

After launch, it would accelerate to 24,000 km/h and set off on its maximum 8,500-kilometer journey, a US guard explained to him, adding, “I'm often asked how big the explosive power of the Minuteman is compared to Hiroshima. But I don't think it compares at all. A better comparison would be with the total explosive power of all the bombs detonated during World War II. Then you have 60 percent of what a Minuteman missile does.” At the time of filming, around 2010, the USA stockpiled around 500 of this weapon system alone.

When the soldier asks his prominent visitor from Russia whether he believes that nuclear missiles will one day be used, in the film Petrov replies, “Yes, I do. It's absurd. History has taught us nothing. We are still on different sides of the same barricade.”

In the early morning of September 26, 1983, in the bunker on his side of the barricade, Petrov now has five approaching Minuteman missiles on his screen. But the image reconnaissance expert still cannot see any of them on his monitor. The alarm siren blares incessantly, red warning lights flicker. The minutes tick by. What is going through Petrow's head? In his mind's eye, according to the movie, he sees ballistic missiles launching and accelerating. “If I confirm the attack now”, he muses, “a lot of people will die. All our armed forces will be put on combat readiness, including nuclear missiles with more than 11,000 warheads. In the army headquarters they will then only have to press a few buttons. No one will dare contradict my assessment. It's easier for everyone to agree with it. And I'm the only one in charge.”

Imagine that: A perfectly drilled member of the Soviet system has just declared the supposed start of World War III by the USA to be a computer glitch. It’s an immensely courageous decision of conscience in view of the possible consequences. And only minutes later he is now facing a second wave of attacks, now four times as strong. In this situation, who has the strength to plead technical failure again? Petrov gives the order to wait for confirmation of the attack from the Soviet ground radar. The problem: Then it is only seconds before the warheads explode over the major cities of the giant empire.

“If I'm wrong,” Petrov thinks at the time, according to his own recollection in Anthony's film, ”millions of people will die. Maybe I should change my decision and follow protocol. Yes, I could do that. But I don't want to be the trigger of World War III! If they really attack us, I want to take that sin on my head. I won't change my decision.” Millions of lives are hanging by a thread in these seconds. “And none of them have the slightest idea,” Petrov says to himself. “I couldn't get that thought out of my head”, he recalled in the movie.

One of those people is me, the then 17-year-old author of this article. I am asleep.

A few minutes later: Now the ground radar has to pick up the signals. Then the message comes: There's nothing! No missiles approaching! Petrov was right to wait until the end. In the film, the men in the bunker hug each other. And the lieutenant colonel on duty bursts into tears. The 17-year-old in Germany tosses and turns in his bed in uneasy dreams.

Under the cover oft the the strictest secrecy, the Soviet Union's military again and again investigated the causes of the technical failure. To this day, the pubished findings remain inconclusive. One source claims that a rare reflection of sunlight in high cloud layers over North Dakota in combination with the highly elliptical orbit of the Soviet reconnaissance satellite triggered the false alarm. Petrov himself states in the film that the reason was never found.

Unlike Barack Obama, who commissioned extralegal drone assassinations many times, Stanislav Yevgrafovich Petrov never received the Nobel Peace Prize. He was even reprimanded by his own generals because he had not kept a complete record during the nuclear crisis. His heroic deed was kept secret for almost ten years and only came to the attention of the global public after the end of the Soviet Union. Perhaps our green, woke and other cheerleaders of warfare should keep this in mind, provided they are old enough: They owe the saving of their own lives and the lives of at least 400 million other people from “mutually assured destruction” to–a Russian. In the 2014 “documentary”, this man, in advanced age, is portrayed as a drunken, neglected wreck prone to vulgar outbursts of rage. When it came down to it, he was anything but.

We must assume that with Petrov’s level-headed response in 1983, humanity's luck ran out. The miracle of preventing nuclear war through human intuition and courage in the face of seemingly overwhelming evidence to the contrary will remain exactly this: a miracle. A deeply human decision like Petrov's is unlikely to be repeated in the comparable stressful situation of an escalating war in Ukraine or the Middle East. Today, the militaries of the modern nuclear powers not only possess “hypersonic” missiles that leave hardly any reaction time. Their security systems are also equipped with artificial intelligence. And an AI knows neither intuition nor conscience.

A German version of this article was originally published in TWASBO Magazine, September 2023.

Greetings from Canada. Great article.